Supplemental page of illustrations for

The Production Code of the Motion Picture Industry web site

From March 1930 to July 1934, the major Hollywood studios were ostensibly self-regulating the contents of their movies and advertisements to keep them “clean” in the eyes of the many puritanical organizations that threatened to force upon the industry censorship from the federal government. Through the industry’s public relations organization, the film studios assured concerned parents and “civic leaders” that they needn’t go to the effort of making government bowdlerize the contents of movies, because the industry would do that for them. However, the studios were ever aware that sophisticated city audiences had proven by their patronage that they liked daring, thoughtful, edgy, naughty and racy movies. The studios were thus caught in a bind, arguing that certain scripts presented such an important reflection of society as it was or as it saw itself going, that a movie should be allowed its violence or marital infidelity or “free love.”

The exceptions granted to studios when they proposed quality, thoughtful projects on difficult subjects proved to be a slippery slope. The studios not granted the first exceptions would argue to the Studio Relations Committee that a rival had been granted a waiver so why not us? When the censors employed by the industry made decisions which a studio sought to overturn, the studio could seek an appeal from a board made up of members from all the major companies. Rival studios were willing to grant an appeal while each believed that when the rival’s own studio next sought an exemption, it would be owed the same courtesy in return.

“Scanning newspapers, handbills and billboards, moral guardians were alerted to the awful doings in films they would never have been aware of otherwise. In 1934, a racy billboard so infuriated Philadelphia’s Cardinal Dougherty that he launched the motion picture boycott that helped bring aboout the Production Code Administration. Outside his residence, a provocatively painted and leeringly taglined billboard for a Warner Bros. melodrama [had] daily affronted his eyes.” (Thomas Doherty, Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930-1934, Columbia University Press, 1999, pages 112-113) “Advertising had always been a flash point because salacious taglines and lush illustrations were incandescent signs of vice. No matter that the films themselves were far tamer than the poster art and exclamatory blurbs; Hollywood sold the promise of immorality and insurrection. An unintended consequence, however, was that influential people who never went to the movies got their main impressions of the screen from the false advertising, the prime example being Cardinal Dougherty …” (ibid., pages 331-332) |

Questioning of Society’s Institutions

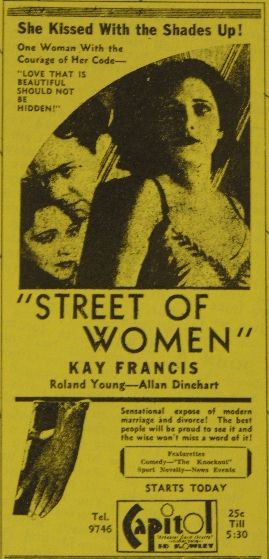

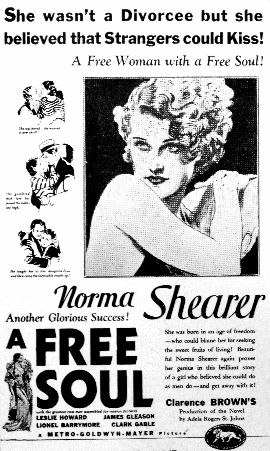

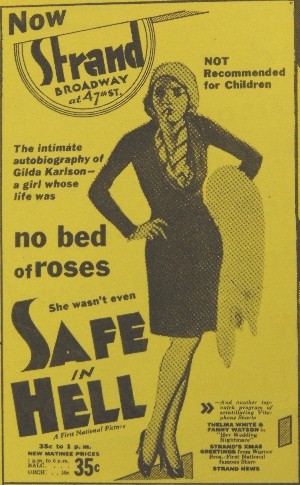

| Advocates of enforcing the Motion Picture Production Code and of not allowing exceptions, sought to uphold the institution of marriage and to deny the movies the chance to dramatize such alternatives as “open marriage,” “trial marriage,” sex before marriage, and other such variations embraced by “modern” thinkers of the time. The next ads shown on this page are examples of ads and movies that challenged the conventional view of sexual morality. |  |

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

Above: The headline incorporates variations on the titles “The Divorcee” and “Strangers May Kiss,” which had been Norma Shearer’s two previous films. In the description for this newest film (see detail at right), we’re told that the young heroine “was born in an age of freedom,” that she enjoys “the sweet fruits of living” (seemingly a eupheminism for pre-marital sex and illicit drinking) and she “believed she could do as men do”—suggesting that she is challenging conventional notions of the double standard whereby men were permitted more lenience in attaining non-marital sex. In the film, Shearer’s character forsakes her engagement to an honest conventional man so that she can instead live a wanton life of late nights in speakeasies with her new gangster boyfriend. (Film released by

| The haughty, insolent posture of Dorothy Mackaill suggests what the film makes clear: she plays a prostitute who is unrepentant about her profession and business-like in her manner of lining up a client. The film itself does depict the cruel aspects of her life: she’s surrounded by leering, crude, criminal men overly intent upon impressing their grimy selves upon her despite her protestations and her desire for privacy. (Film released by Warner Bros./First National, 1931) |  |

Sin as Fun and Irresistible

|

Nancy Carroll’s open top is a hint of what occurs in this 1932 Paramount release. | |

|

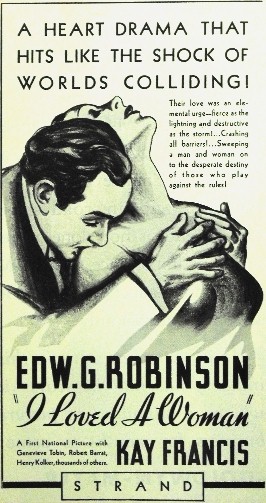

Edward G. Robinson’s tawdry pawing of Kay Francis in this ad is the type of action which raised the ire of reformers when I Loved a Woman was released by Warner Bros./First National, 1933. |

Questions in ads

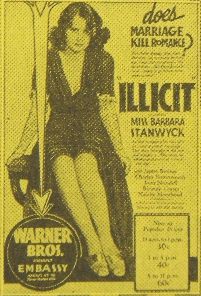

During the 1930s and 1940s, questions were sometimes posed in movie ads and on posters. In asking “Does marriage kill romance?,” the ad for Illicit (Warner Bros., 1931) raised the same type of challenge to the institution of marriage as earned the ire of reformers described further up this page.

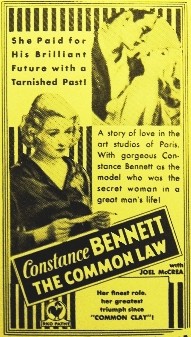

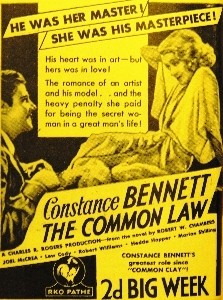

Sin: Thy Name is Bennett

|

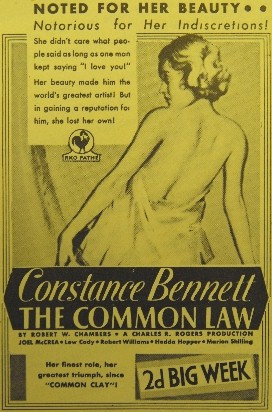

Three different ads for one drama starring Constance Bennett (left, below left, below right). When released in 1931 by RKO, audiences had the previous year seen Miss Bennett in a film with a title beginning with “Clay”: Common Clay. (An ad for the 1930 film with ignominious content appears elsewhere on this web site.) |

(right:) Constance Bennett in bed attire. She’s pictured here with Neil Hamilton. (RKO release, 1932) |

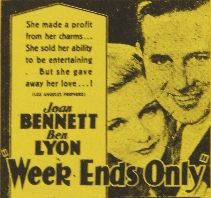

| Joan Bennett may have not intended this, but she proved that her sister Constance didn’t have a monopoly in her family on starring roles in movies advertised with racy ad copy. (This movie: Fox Film, 1932) |  |

|

Women’s Chastity Surrendered

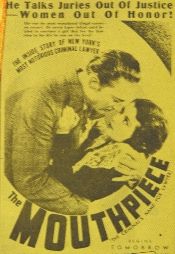

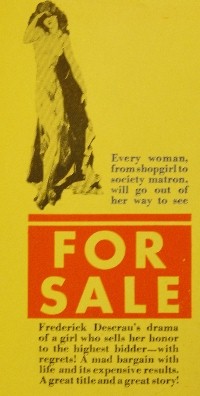

“Mouthpiece” was a slang term for a criminal’s lawyer. The Mouthpiece (Warner Bros., 1932) starred Warren William as a lawyer who uses flashy and deceptive techniques to win acquittals for clients he knows to be guilty. The ad line “He Talks Juries Out of Justice—Women Out of Honor!” refers also to his having designs on the his secretary, who proves innocent in a sense different than applicable to his clients. For Sale was announced in Spring 1931 but not made.

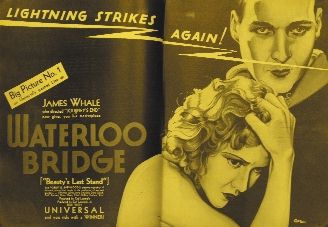

Two More Scurrilous Ads

Nothing more is needed to set off the imaginations of persons seeing these ads. Both films star actresses known for quality, sensitive films.

Quality Films, Lascivious Advertising

|

The Animal Kingdom (RKO, 1932) has Leslie Howard married to Myrna Loy (both pictured at left). Loy’s plunging neckline would not have been allowed in a magazine ad for the film had the ad been placed after the Production Code Administration clamped down in mid-1934. The film was a sophisticated drama from a Philip Barry play, with husband Howard becoming reacquianted and re-enamored with Ann Harding, with whom he had lived out of wedlock prior to his marriage to Loy. The film prompts viewers to ask whether Harding was more truly Howard’s wife, quite apart from wedding ceremony and marriage certificate. | |

|

The original version of Waterloo Bridge (Universal, 1931) had the most mature approach toward the romantic relationship between a sexually-naive soldier (Kent Douglass) and his much-experienced girlfriend (Mae Clarke). Although the ad suggests her possible nudity, the story is more about her emotional nakedness and his willingness to accept her past. |

This page is part of the Production Code of the Motion Picture Industry web site

© 2009 David P. Hayes